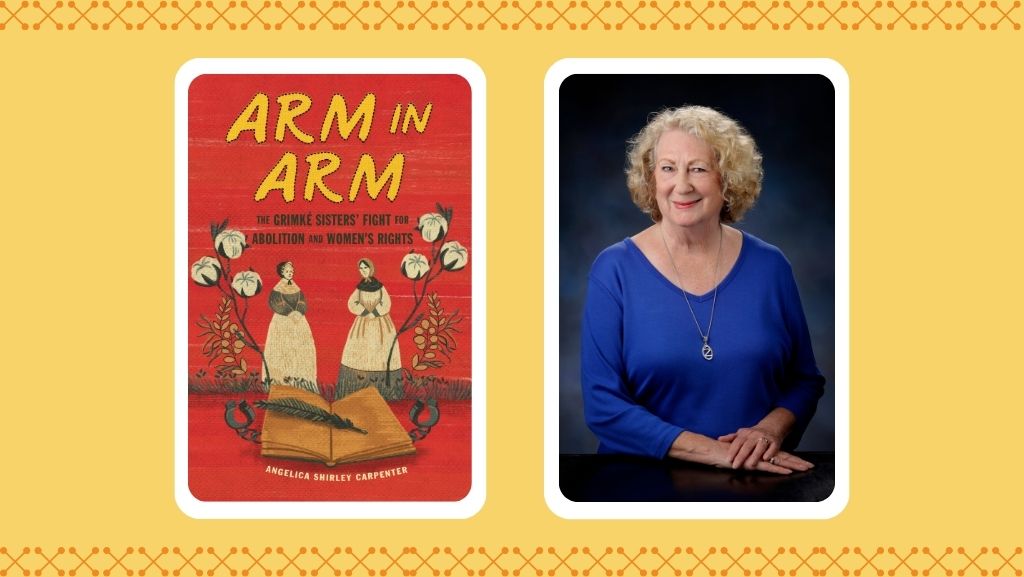

Arm in Arm: An Interview with Author Angelica Shirley Carpenter

As historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich said, “Well-behaved women seldom make history,” and the Grimké sisters were anything but well-behaved. Born into a family of enslavers in the South, Sarah Grimké and Angelina Grimké Weld were some of the first women to speak out about abolition and women’s rights. Arm in Arm: The Grimké Sisters’ Fight for Abolition and Women’s Rights explores the mostly forgotten lives of these complex women leaders.

Today author Angelica Shirley Carpenter joins us to share her source of inspiration for this YA nonfiction, her research process, and some of the most surprising finds.

What inspired you to write this book?

My previous YA biography was Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist. Matilda was a leader in the women’s rights movement from 1852 to 1898. She was an organizer, a speaker, a well-known author, and the most radical women’s rights leader of her time. The first volume of the History of Woman Suffrage (1889), which Matilda wrote with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and published with Susan B. Anthony, was dedicated to the sisters and other earlier leaders who had passed away. The book devoted twenty-two pages to the sisters and their work. In her most famous book, Woman, Church and State (1893), Matilda also wrote about how the sisters, telling how Congregational ministers attacked the sisters in a pastoral letter, calling them “unnatural” women for speaking in public. I wanted to find out what these women had done to inspire Matilda and others.

How do you do the research for a book like this? What are your writing habits?

There are many books about the Grimkés and I think I read them all. I also read histories of the time and biographies, autobiographies, and published letters of their famous friends. These secondary sources led me to primary sources, which were listed in the books’ notes and bibliographies. Many of the sisters’ letters have been published and much of their own writing is also easy to obtain. I’m lucky to live in a university town with an excellent library. The Fresno State Library has a collection of more than a million books and more often than not, when I want a particular book, it is there on the shelf. If not, as faculty emeritus (I worked as a librarian there), I have interlibrary loan privileges and that department has tracked down many other resources for me. As retired faculty, I have access to all library databases from my office at home, including sites like JSTOR and America’s Historical Newspapers. Newspapers were an important part of my research; often I used the Library of Congress’s “Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.” Some papers, like The Liberator, are free to read online. Then I used Google Scholar and Google books, or just Google, casting a wide net. Internet research can be rewarding or frustrating. Even if materials, especially handwritten documents, have been digitized, they are sometimes impossible to read.

As I read these research materials, I take notes in Word in chronological order. I also compile a file of photographs and other illustrations to share with the publisher. As the author, I must obtain permission (and pay for the right, if required) to quote copyrighted materials. For this book, the publisher acquired the photos and illustrations, paying any necessary fees, but I did a lot of photo research myself. After all, pictures are primary sources, too.

So are places. In the fall of 2024, my husband and made a Grimké-oriented pilgrimage to Charleston. It gives an author, or this author, at least, a giddy feeling to stand in places she has been writing about. Sometimes the experience brings corrections or new facts. Jude Kellison, a docent at the Heyward-Washington House, Sarah’s childhood home, now a museum, gave me a better understanding of rice farming: The enslaved workers had to fight off not only alligators (I already knew that) but also water moccasins. Well, I knew about snakes, but to have this specific name really helped make the experience, and the book, seem more real. Exhibits at the Charleston Museum and the new International African American Museum gave me a wonderful feel for processes, customs, and artifacts of the time.

For me, and maybe for all librarians, research is the fun part. We are likely to get caught up in “research rapture,” continuing to compile information beyond what we need. It takes willpower to stop looking and start writing, but once I do, I love the writing, too. I write all day unless I have some other obligation, and knock off about 5 for a game of Scrabble with my husband.

What did you learn that surprised you?

I had a pretty good understanding of their lives and accomplishments from early reading. What interested me especially were the personal details: the way, if they didn’t know something, like how to keep house or how to care for a baby, they consulted advice manuals. I loved it that Angelina watched for Theodore’s boat and blew a whistle when she saw it, and he blew one back. Theodore could be quite bossy, so I enjoyed reading, from his point of view, how Angelina stood up to him about buying the sleigh. I was surprised to learn how physically active all three were, going on “rambles” and dancing, even into old age. It was fun to picture Sarah, who looks rather grim in pictures, having “romps” with her nephews. And I loved it that she sat in the chief justice’s chair and imagined a woman holding that office someday. I enjoyed reading about them from their friends’ points of view and it pleased me that their friends wrote funny verses about them.

What do you hope that readers will learn from reading your book?

I imaging that many of them will learn about the horrors of enslavement as well as about the bi-racial abolition movement. Many people are surprised to know that enslavement was popular in the North, as well as the South, and that pro-slavery mobs killed abolitionists even in northern states—they murdered people who wanted freedom for all. With their personal stories of enslavement observed, the sisters shocked many Northerners and their reports surprise and outrage today’s readers, too.

Perhaps in this book they will learn about the beginning of the women’s rights movement for the first time. Many people today do not realize how restricted women were in the early 1800s, unable to vote, serve on juries, attend colleges or universities, work in most professions, testify in court, sign contracts or own property (married women), win custody of their children in divorce cases, or even to speak in public. Even young people will be aware that many elements of racial prejudice and misogyny continue to this day and that rights considered won, like freedom from illegal seizure and deportation, or even murder, or the right to abortion or birth control, can easily be lost. I hope they will learn how to stand up, speak out, and fight back.

What makes this book different from other books about the Grimkés?

As I said in my afterword, books and opinions about the Grimkés go in and out of style. In the twenty-first century, the sisters have been largely ignored, though they are starting to be included in collective biographies about the women’s movement. There are good young adult books about the sisters, especially Angelina Grimké: Voice of Abolition by Ellen H. Todras (1999), and many good books written for adults. My book differs from these in that I tried to create a balance between their professional and personal lives, using their own words, and the words of their friends, to describe them and their actions. One of the main differences in my book is the quotes—proportionately there are many more than in the other books, including quotes from newspapers that have not been reprinted since they were originally published.

Praise for Arm in Arm

“This relatively short book thoughtfully presents a period of upheaval and change and traces the sisters’ long-lasting impact as well as recent, more critical perceptions of their motivations and behavior that bring welcome nuance to their story. . . Informative and insightful.”—Kirkus Reviews

“Peppered with black and white images, Carpenter’s understated, straightforward writing is informative and engaging and keeps the pages turning. Her detailed research is documented with extensive source notes. . . Covering the entirety of the Grimké sisters’ lives, this is a thought-provoking biography of two fierce yet humble abolitionists who deserve more attention than history has given them. Recommended for all libraries.”—School Library Journal

Connect with the Author

Angelica Shirley Carpenter‘s recent titles include a young adult biography, Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist, and two picture books, The Voice of Liberty and The Secret Gardens of Frances Hodgson Burnett. Her 2025 young adult biography is Arm in Arm: The Grimké Sisters Fight for Abolition and Women’s Rights. Curator emerita of the Arne Nixon Center for the Study of Children’s Literature at California State University, Fresno, she is a past president of the International Wizard of Oz Club. She has master’s degrees in education and library science.

Comments