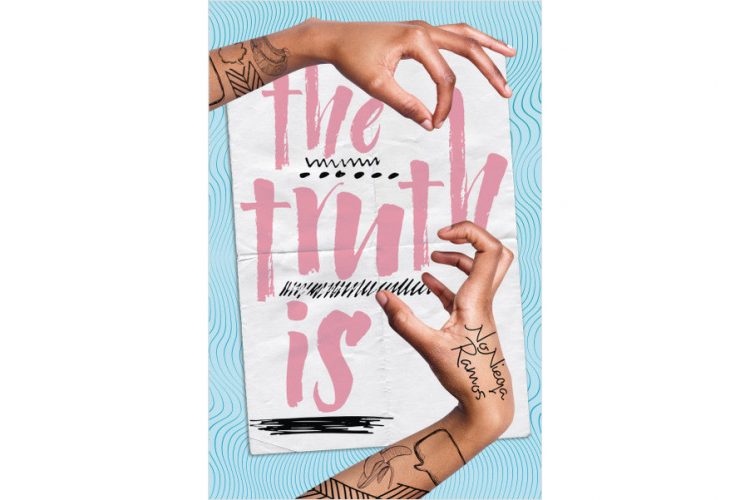

NoNieqa Ramos on Coming Out in YA Literature

by Amy Fitzgerald, Editorial Director, Carolrhoda Books

In honor of National Coming Out Day on October 11, I talked to author NoNieqa Ramos about LGBTQA+ advocacy and representation in YA literature.

In your new novel, The Truth Is, no character has a smooth or joyous coming-out experience. The Underdogs have been outright rejected by their families. Verdad’s mother is furious that Verdad is dating a trans guy, because she thinks it means Verdad is a lesbian. (Verdad eventually realizes that she is, in fact, pansexual—attracted to people of all genders.) Yet the kids do encounter understanding, accepting adults. What led you to include Mrs. Joung, Mr. and Mrs. Maheshwari, and even that priest in the story?

I wanted to acknowledge—and combat—the struggles of LGBTQIA+ youth, but also present hope. Hope is real. Rejection by some or even many doesn’t mean rejection by all. There are family members, neighbors, teachers, religious leaders, librarians, and people in the community—or outside of it—who can offer support and understanding. I truly believe every queer kid has a queer family out there.

I also wanted to present a nuanced representation of Korean-American and Indian-American culture, particularly when it comes to LGBTQIA+ issues. That’s why Mrs. Joung and the Maheshwaris approach the Underdogs with compassion and acceptance. The priest who speaks to Verdad shows up because while religious institutions have been problematic, allies and refuge can exist there too. I myself have seen great love, respect, and support of LGBTQIA+ youth in the Unitarian Universalist church. LGBTQIA+ youth deserve to have access to religion and spirituality and just like everyone else.

One of my favorite characters is Verdad’s aunt Sujei. Tia Sujei doesn’t really understand LGBTQA+ identities or issues, so she says plenty of ignorant and hurtful things. But unlike Verdad’s mother, Sujei is willing to have a conversation—and she doesn’t threaten to withhold her love from Verdad because of who she is. That’s a different kind of challenge for Verdad than, say, being disowned would be. What would you say to teens who want to come out and know they’ll receive a loving but imperfect, perhaps still painful, response from adults in their lives?

To Whomever Needs to Hear This:

It’s complicated. You’ve got people accepting you in fractions. Maybe someone you care about doesn’t understand your queer identity. You might be having tough conversations. You’re hurt and disappointed. But you don’t want to give up on the relationship yet. They don’t want to give up on you. There’s a lot of confusion.

If that’s happening, I hope you can find another trusted person to give you counsel and support to get through it. If you can’t, please remember that anyone accepting you for anything less than 100 percent you is coming from a place of ignorance or weakness, and ultimately they will be in the minority of people you meet in your life. Hold on. The world gets so much bigger.

If you want to forgive someone because they have overcome their ignorance, do it. You are amazing! I would forgive my father in a heartbeat.

That being said, know for a fact that no adult’s beliefs or biases invalidate your personhood. I’m sorry you have to tolerate anything less than unconditional respect and love. You have every right to end a relationship with anyone—including a relative—who doesn’t accept your identity.

My biggest message is not to reject yourself. Take care of your body, mind, heart, soul. It may take time, but surround yourself with people who will do the same. You deserve it, we are out there, and we accept you as the whole, dynamic person that you are.

You’ve been a teacher for a long time. What have you noticed about how your students express their identities and respond to one another’s identities? What challenges do you see teens facing when it comes to seeing and being seen among their peers?

I can answer this with a story. Trigger warning: bullying and self-harm.

Last year, a group of students and I organized Pride Week activities at our school. Each day we’d wear a different color on the rainbow. My classroom was a Pride Pit Stop where kids could meet, grab snacks, get flags and stickers, and take pics.

At a middle school in the same district, my friend’s trans child, let’s call them Marta, was enduring relentless bullying in the halls, whenever they went to the bathroom, at gym class, and on the bus home. They weren’t sleeping. Marta’s mom tried to talk to the bully’s mom but got a hostile response.

That week kids all over my school wore the color of the day, sported student-made pronoun labels, and waved flags. At one point, a student came up to me and said, “Kids are saying I’m gay because I’m wearing the colors.” I said that the color can mean you’re gay, or it can mean you’re ally to gay people. It’s cool if you’re gay. It’s cool if you’re not. Does it bother you if someone thinks you’re gay?

He shrugged, smiled, said I guess not, and went to class. I alerted some of my student organizers that this student may need some emotional support. The next day, I was thrilled to see that he dressed out again. In another incident I’ll never forget, a student I’d never met walked into my class, took a sticker, and said, “I’m autistic and bisexual. I just wanted to tell someone that. You are the someone.” Even as I reveled in moments like this, some members of my team said they were getting bullied. I offered to escort kids to classes.

Back to Marta. Their mom connected them with LGBTQIA+ allies in the community and a counselor who specialized in LGBTQIA+ issues. But when Marta finally lashed out at the abuse from the bully, they and the bully got suspended.

That Thursday, I was escorting one of my LGBTQIA+ students through the hall when I was told over the PA to report to the principal’s office. “It’s because of us,” the student said. Pride Week was shut down.

Shortly afterward, one of my fellow teachers—a lesbian who had gotten married the week before—told me she loved Pride Week and had come out to one of her students. So why did she only come out to only one student? Why hadn’t she done what EVERY straight (or straight-presenting) teacher does after a wedding—fill her PowerPoints and her desk with photos and mementos?

She and her spouse were afraid of the reaction of our conservative community. They were afraid of losing their jobs.

Progress is happening, but it’s inconsistent and uneven. Which means safety for kids—and adults—is inconsistent and uneven.

Again, there is hope, but we cannot be complacent. There is still so much work we need to do on behalf of our kids. That’s why it’s so important to give all kids access to LGBTQIA+ resources and easily identifiable allies, so that if and when they identify, they have support right away.

When I was a YA reader ten or fifteen years ago, I never came across a coming-out story. Now, I can think of quite a few—some harrowing, some sweet, most ultimately empowering. (I think The Truth Is is all three, though I’m biased.) But many people don’t feel safe or comfortable coming out to everyone in their lives, and it’s worth noting that there’s nothing cowardly or inauthentic about this. What are your thoughts on how YA literature can support and validate teens who are fully or partially “in the closet”?

We need to do for queer children’s literature what we’ve started to do for literature by people of color: analyze it statistically on a yearly basis to establish how far we’ve come and how far we need to go to accurately represent the diversity of the LGBTQIA+ experience. Let’s gauge it by the numbers. Exactly how many stories are we giving kids that are fraught but ultimately hopeful, that are fun and exuberant, or that rep kids who are partially in the closet? Kids need them all. When we give them a balanced representation of the queer experience, we’re giving them an array of possibilities that they can consider from the safety of a book.

I also think more nonfiction needs to be produced by #ownvoices LGBTQA+ writers, who can help guide kids through safely making decisions about being in, completely out, or partially out of the closet. And more nonfiction needs to represent successful and openly gay persons who are happy and living their best lives. So the answer is a balanced diet, larger portions, and always dessert when it comes to rep in lit.

Comments