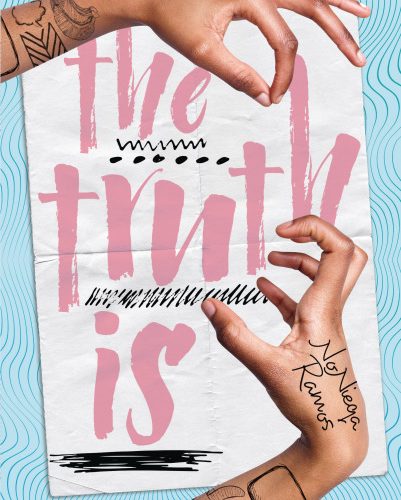

NoNieqa Ramos on Decolonizing YA Literature

Today, we have a guest post from NoNieqa Ramos.

Authors from marginalized groups often talk about the fine line between speaking the truth of one’s experience and being tasked with the emotional labor of enlightening or educating people outside that group. How do you navigate that line?

To speak plain: White people relying on people of color to do the emotional labor of educating and enlightening them is generally unacceptable. I say generally, because it depends on the setting. Por ejemplo, a school or job providing equity training is the time and the place for white people to seek edification. But what about my character Verdad, a queer person of color whose school has not decolonized their syllabi or their culture? What about Verdad, who is being raised by homophobic and transphobic people like I was? We have all been drinking from the poisoned well of hegemony, and tragically, in many cases, if children don’t drink from that well, they ain’t getting any water at all.

I open my book by showing that the school Verdad attends is toxic. Verdad starts her own edification after hearing from Nelly, an Afro-Latinx girl who takes a stand against hegemony—and faces the consequences for it. She’s also forced to rely on her new family of friends, queer people of color, to wake her up. And I equip Verdad to edify herself. This girl ends up carrying around a backpack of reference books about her culture.

Of course, she already knows that white supremacy is real and deadly; she lost her best friend to a racist mass shooter. But it takes her time to get that we all have internalized racism and homophobia.

Queer people of color like Verdad—even with all the pain we’ve suffered—need to examine how we may perpetuate unconscious bias against other queer people of color. We have been taught to hate each other, to hate ourselves, by the society we live in. It goes back to the poisoned well. I wrote The Truth Is to reflect that journey.

So, no, queer people of color do not exist for the edification of cishet white people. But paradoxically, without us, without our work and our activism, what would our world look like?

Is there tension between the urge to present the image of a “model minority” and the inclusion of flaws within your characters?

I’m trying to picture what a “model minority” is like. Probably brilliant, because marginalized people have to work twice as hard to get half as much. Probably an activist. My character Verdad has PTSD, and the idea that she has to be an activist overwhelms her. She shrinks—hides—from the implicit responsibility. While my book celebrates the sacrifices of activists, it also calls into question the idea that every POC has to be one.

Maybe a “model minority” must be woke at the outset. Verdad isn’t. Her ignorance is harmful to Nelly and to her homeless friends. Layer by layer, she realizes that the lens she views the world with is warped.

As I wrote the book, the pressure to make Verdad into that “model minority” was overwhelming. I could have simply focused on the racism against her and her friends. But I wanted to represent the complex world we live in, where children like Verdad are besieged by white supremacism yet also breathing its air.

I knew I took a risk writing her. What I wanted was to start discussions about important truths. The truth that queer people of color live in a dangerous world founded on oppressing them. The truth that we, the victims of that oppression, have been conditioned to perpetuate it. And the truth that once we understand systems of oppression, we can dismantle them. Kids are at the forefront of this revolution, and books are the greatest tools we can give them.

What does decolonization mean to you?

Decolonization means deconstructing the dominant narrative of white European men. Hegemony has tried to brainwash people of color into believing their truths are folklore and fairy stories, while the white man’s narrative, the narrative of the colonizer, is fact. History is enriched with the accomplishments of POC and stained with how these accomplishments have been appropriated. Decolonizing literature means that the books on the shelves represent empowered persons of color telling their own stories from their own perspectives and own cultures.

Decolonization means no more romanticized, whitewashed narratives that conceal how racism is born from economic greed. No more imbalances where books only represent the pain of POC and not the joy and complexity and nuances of family and culture. No more using the idea of multiculturalism against POC to pretend their contributions were freely given. It means an America that comes to terms with its painful past to give our children an equitable future.

Do you have any tips for helping readers experience discomfort?

In The Truth Is, just when issues of equity and justice are about to be discussed in class, the teacher steps out of the room. I wrote this scenario intentionally. So often, educators are not present. School boards and administrators may place limitations on what educators can teach. Maybe, as I’ve experienced as an educator, they can have LGBTQIA+ books on the shelf but not actively use and discuss them in the classroom. Maybe their school board is arguing against LGBTQIA+ protections altogether. Maybe there isn’t equity training at a school, so educators don’t know that POC rights and LGBTQIA+ rights are human rights and nonnegotiable.

I advocate for educators to be in the room and at the forefront of these uncomfortable discussions. Schools need to provide equity training and support, and teachers need the tools to respect and nurture their students with crucial conversations, informed by a wide range of diverse #ownvoices literary fiction and nonfiction texts.

But back to all readers, with or without educators guiding them. We ALL need to get comfortable being uncomfortable. Any of y’all exercise? Are you ever going to get anywhere physically if you never get uncomfortable? To expand our minds, we have to stretch, and that’s gonna hurt, but it makes us healthier. It means we can take the stairs—maybe to the top floor—and catch a view we never imagined.

My advice is to take a deep breath and to know you are not lost in the wilderness. Follow the leaders behind the movements for equity, like Dr. Debbie Reese, David Bowles, and Las Musas. Read books like White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo and Michael Eric Dyson, How to Be an Anti-Racist by by Ibram X. Kendi, and An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. Develop self-reliance in your edification. And if you still mess up? Apologize without expecting forgiveness.

If you’re asking yourself why do all this? The kids are the answer.

—

More from NoNieqa Ramos: On Writing Diverse Characters and Resisting the Status Quo

Comments